Telemedicine’s Legacy and Future

While many of us became familiar with telehealth over the past four years, UVA Health has been at the forefront of the practice for three decades and today is the hub of a 153-site statewide telemedicine network supporting upwards of patient encounters per year. A lot has changed since the original program launched in 1994.

“We launched our telemedicine program because of our recognition that so many patients had challenges accessing our specialty providers,” said Dr. Karen Rheuban, a pediatric cardiologist and professor at the University of Virginia School of Medicine and co-founder and Director of the UVA Center for Telehealth, which now bears her name in recognition of her work.

“The University of Virginia traditionally served patients in the western half of the Commonwealth of Virginia, which extends to the far southwest corner of Virginia, which is in fact as far west as Detroit, Michigan,” said Rheuban. “For many decades, my pediatric colleagues and I traveled to Bristol, Virginia, to see patients every other month. With that came the recognition that in between our visits, it was a hardship for our patients to travel to Charlottesville to access our care. That was the genesis of the development of our telemedicine program.”

Advances in personal computing and increased broadband availability enable virtual office visits delivering care to individuals and families who would otherwise have to travel long distances for specialized needs. Source: UVA Health.

Specialty medical care such as neonatal care, pediatric and adult specialty care, and other services such as acute stroke intervention or high-risk maternity care has always been more accessible in urban areas and municipalities with established medical schools, such as Charlottesville, home of the University of Virginia. For rural patients, there are often sufficient numbers of primary care providers, but accessing specialized providers is a challenge due to the travel time necessary to reach them.

In The Beginning

“Thirty years ago, we launched our telemedicine program to provide improved access to specialty care from healthcare facilities such as hospitals and clinics. Medicare and Medicaid regulations related to reimbursement required patients to be at healthcare facilities. Of course, most homes were not equipped with connectivity to support telemedicine encounters,” said Rheuban. “At that time, few patients or providers knew about telemedicine and broadband was certainly a far cry from ubiquitous.”

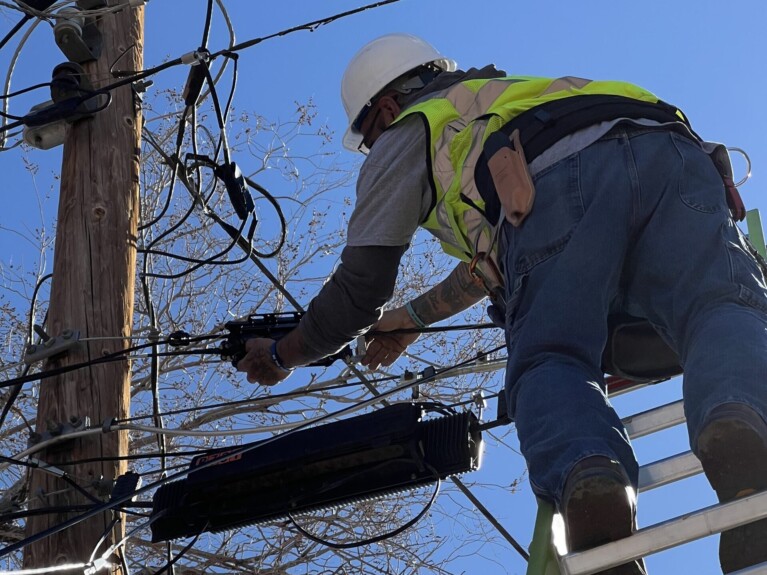

Establishing on-site rural telehealth facilities in the mid-90s was no trivial task. Running a (then) state-of-the-art 1.54 Mbps T-1 connection to a southwest Virginia community hospital or health center cost $6,000 per month, along with $150,000 per site for networking and proprietary video equipment. Electronic medical records (EMR), if they existed, had to be accessed through a separate dial-up process.

“It was an environment where there was little to no reimbursement of telemedicine services, and a lack of understanding of the applicability of telemedicine both by patients and by providers,” said Rheuban. “However, when patients began to use telemedicine, even as far back as the mid-1990s, the value and convenience was clear. After testing a telemedicine link to a remote community hospital, my longstanding patient’s father said, ‘Tell everybody that if I don’t have to drive back to Charlottesville, I’m never coming back. I want all my son’s care to be this provided this way.’”

Navigating technology, pricing, and payments weren’t the only challenges UVA faced as it built and established telemedicine standards. The regulatory environment had to be modified as well to permit the practice.

“Early on, every provider who was to deliver a telemedicine service to a hospital, contractually would need to be fully credentialed and privileged at that hospital,” Rheuban said. “You can imagine what it would take for a 25-bed rural critical access hospital to credential and privilege 1,000 UVA providers; a huge amount of work and a gigantic burden. We were very fortunate to work with the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization (JCAHO), now known as the Joint Commission, and CMS to facilitate new regulations that enabled credentialing and privileging by proxy. In other words, if I’m credentialed and privileged at the University of Virginia, the medical staff of a community hospital could elect to accept my credentials by proxy. That policy change eliminated a huge burden for telemedicine providers and patients originating at site hospitals as well.”

The Pandemic Accelerator

Telehealth is incredibly important today in terms of delivering health care and contributing to better outcomes – in other words, making people better and keeping them out of the ER and hospital when not needed, along with saving patients time and money. Any topical discussion about telemedicine goes hand in hand with the changes in regulation and mindset that took place during the pandemic, when face-to-face meetings with a doctor or a visit to the ER for anything except the most necessary critical care were discouraged.

Telemedicine emerged as a necessary lifeline for doctors and patients alike. “The COVID-19 public health emergency truly transformed telehealth,” said Rheuban. “Those of us who were already using telemedicine were able to rapidly scale to provide services across all the disciplines, and not just for specialty care, but also for primary care. That was probably the one blessing of the COVID-19 public health emergency…scaling up telemedicine. We learned a lot during the last four years in terms of utilization, technology, integration, broadband, and what works, what doesn’t work. And hopefully, as we scale our broadband infrastructure, access to telehealth becomes available to every patient – wherever they are located. And adopted by every provider and health care facility as well.”

Public policy waivers issued during the crisis enabled health care organizations to implement telemedicine service more broadly and integrate them into everyday care, particularly since Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial insurance companies issued waivers that enabled reimbursement for telemedicine services, regardless of patient location. That being said, Congressional action is necessary to make those changes permanent.

“Policy changes at the state and federal levels exponentially increased the availability of telehealth services to patients. Reimbursement is critical for adoption by providers, and broadband is critical to patient engagement and a high-quality encounter,” said Rheuban.

Better and faster bandwidth to health care facilities and homes delivered via fiber has opened a wider range of uses, including early access to care in the home, a possibility that was literally science fiction when UVA first started its telehealth program three decades ago. Virtual telemedicine visits are now integrated with electronic medical records, patient portals, scheduling systems, peripheral devices, and remote monitoring tools.

Today, UVA Health conducts approximately 8% of its ambulatory visits via telemedicine across all specialties and via many different modalities. Although down from 30-40% of visits during the peak of the pandemic, the transition to virtual care is here to stay.

Prior to COVID-19, the use of telemedicine saved UVA Health patients more than 35 million miles of driving. “We stopped counting after the public health emergency when we scaled telemedicine exponentially,” Rheuban added.

“Nearly every specialty can incorporate a form of telemedicine in its care delivery model. The modalities range from synchronous telemedicine supported by real-time video to asynchronous evisits conducted through a patient portal and econsults between providers,” Rheuban said. “Telemedicine facilitates earlier access to care, and remote monitoring programs allow for the monitoring of vital signs obtained at home and tracked by the care team to enable timely interventions and better outcomes.”

FBA Board Member Kimberly McKinley with University of Virginia Center for Telehealth’s Dr. Karen Rheuban discussing about how fiber is essential for telemedicine and the future of health care. Source: FBA.

Delivering mental health service using broadband in the home has grown in utilization and offers some advantages compared to a traditional office visit, Rheuban said. “Behavioral health visits represent one of the most utilized of all telemedicine services. Some say, ‘Think inside the box’ because the video connection is often non-threatening for patients, reduces no shows, and helps to maintain continuity of care.”

Higher broadband speeds enabled by fiber have significantly expanded the tools beyond simple video consultations between doctors and patients, enabling a telemedicine wave of specialized care available to hospitals regardless of location. There are many reasons to deploy and integrate telemedicine solutions in both rural and urban settings, to make the right care and right provider available at the right time to the patients that need them.

“We have deployed technologies to hospitals that require significant bandwidth,” said Rheuban. “Hospital-to-hospital, and hospital-to-clinic services require more bandwidth than does a home telehealth visit because of the need to transmit large files necessary to manage higher acuity conditions. For example, in a telestroke encounter, we require high-quality video to enable detailed patient examinations and expeditious review of CT scans and other imaging modalities to render an opinion and initiate care when every second counts.”

There is still a need to ensure sufficient reliable high-speed broadband availability across the spectrum of care — from in-home services, to care through local clinics and hospitals, and through facilities providing specialized care. Not every condition can be treated virtually, particularly when hands-on care and ancillary services such as imaging, laboratory testing and procedures are required.

Rheuban noted that there are communities 20 miles from Charlottesville that don’t have sufficient bandwidth to avail themselves of telemedicine services, forcing patients to drive back and forth for care. “We are exploring the feasibility of alternative access points for patients if they don’t have access to broadband in their homes,” said Rheuban.

Preserving and extending many of the advancements gained following the COVID-19 public health emergency will require more legislative effort. Making permanent the Medicare telehealth waivers put into place during the COVID-19 public health emergency represents a priority for patients and providers alike. The Medicare flexibilities currently extend through December 31, 2024, and require Congressional action to be made permanent.

Other policy considerations include licensure, which is a function of the states, and to ensure equity in access, the deployment of ubiquitous broadband. Federal BEAD funding is rolling out to the states for broadband expansion. A number of federal agencies have taken additional leadership roles, such as the FCC, USDA and HRSA, in expanding telemedicine services.

“We’ve worked with the FCC in their universal service programs and the USDA to scale telemedicine to rural and underserved communities,” said Rheuban. “The Rural Healthcare Program and the Affordable Connectivity Program enabled providers and patients to secure bandwidth, and under certain circumstances, covered the acquisition of devices. These programs impact low-income and rural patients who truly need [broadband] as a health equity consideration.”

In partnership with state and federal policymakers, Rheuban sees an ever-expanding future for telemedicine. “Patients and providers have become very comfortable with telemedicine following the public health emergency. The evidence is clear – telehealth IS healthcare in the 21st century, and with universal broadband access, we can deliver on the promise of connected care.”